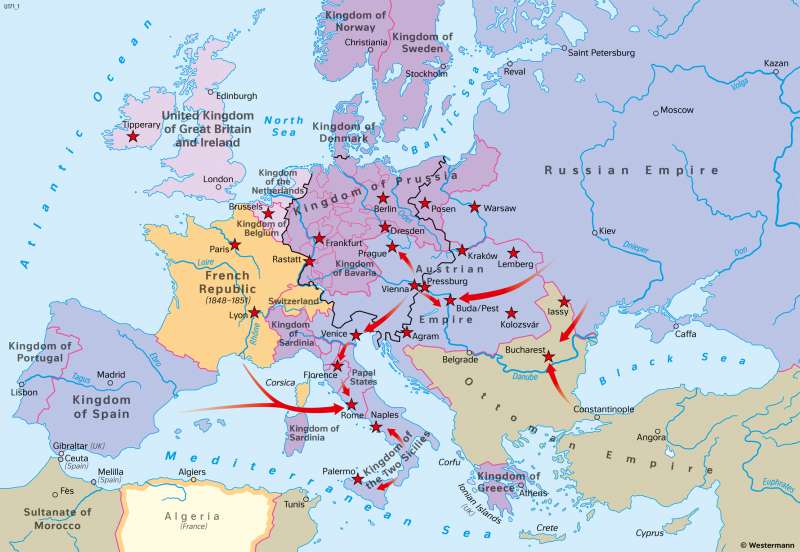

Europe - Revolution and Reaction (1848/1849)

The Modern Era

978-3-14-100890-6 | Page 61 | Ill. 4

Overview

No event shaped the emergence of nationalism in Europe to such an extent as the great revolutionary year of 1848. With its beginnings in France, the revolutionary tendencies ignited in part far beyond Germany, Italy and Austria. The hope for reforms, national unity and independence from the existing power structures was to be violently stifled in many places just one year later. But the awakened nationalism could never be put to sleep again.

Europe before 1848

One of the most noteworthy developments of the modern era was the emergence of the nation state, a process that had begun in Spain, England, and France as early as the 14th and 15th centuries but did not unfold until much later in Germany and Italy. Thomas Hobbes' concept of the social contract and the absolute power of the sovereign provided theoretical justification for absolute rule by princes and monarchs in the 16th to the 18th centuries. A no less significant aspect of the dawn of the modern era was the development of a new economy supported by the middle class, which led to the expansion of trade and the division of labour in manufacturing. Beginning in the 16th century, this early form of capitalism was accompanied by a new work and business ethic characterised by a frugal lifestyle without luxury, which progressively turned against the ruling, though increasingly superfluous, nobility in the course of the following decades. The invention of the steam engine in 1769 set the process known as the Industrial Revolution in motion, which gave rise in turn to a fundamental restructuring not only of working methods but of social life in general.

Reaction

The reaction in the form of military force was launched in April 1848. Revolts in Bohemia, Poland, Hungary, and Italy were suppressed by government troops. The resistance of workers in Paris was broken in June, and the recently introduced ten-hour workday was rescinded. Revolutionary Vienna was reconquered by the army and the Austrian parliament was dissolved in October. In November 1848, General von Wrangel occupied Berlin with an army of 50,000, disarmed the popular militia, banished the constitutional assembly from the city and dissolved it shortly thereafter. Smaller uprisings in many German cities were also suppressed with military force. A "people's army" formed in southern Germany in 1849 was also forced to capitulate in July. An unprecedented wave of persecution involving such drastic measures as summary executions and long prison sentences followed. The revolutionary movement failed in nearly every country in Europe and gave way to the revitalisation of conservative forces.

Revolution of 1848

The German Revolution of 1848/49 was part of a pan-European revolutionary movement that spread to nearly all regions of the continent. Armed conflicts arose in France, Italy, Bohemia, Hungary, Austria, Poland, and the countries of the German Confederation. The causes of these revolts were various. In Poland, Austria, Hungary, and the German countries, they involved primarily uprisings in opposition to the political restoration. Nationalist and democratic movements were suppressed. Social causes played a more significant role in France. During the February Revolution, workers and radical students revolted against the conservative bourgeoisie. The rapid and expansive spread of the revolutionary movement of 1848 was an expression of the troubled economic situation of the lower classes. The onset of the potato blight in Flanders and Ireland had caused severe famine and taken the lives of hundreds of thousands. When the grain supply threatened to break down in 1846 following a series of failed harvests, the crisis came to a head virtually all over Europe. In 1847, a crisis resulting from overproduction and surplus that began in England led to a collapse of the textile and machine tool industries. While food prices rose to record levels, wages fell by roughly one-third and countless people were rendered redundant. That same year, many cities experienced hunger uprisings and strikes, outbreaks of plundering and attacks on food shipments, markets, and bakeries. The conflict between industrial growth and the increasing misery suffered by the working population was exemplified by the Weavers' Revolt in the Prussian province of Silesia in 1844, an uprising that was quashed with military force.