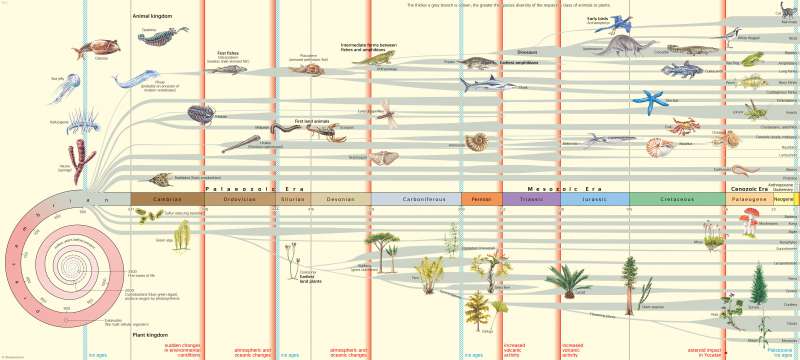

Geologic time scale and tree of life

The History of the Earth

978-3-14-100890-6 | Page 12 | Ill. 2

Overview

This tree of life shows a horizontal scale of the Earth's history in the middle. In the upper half you can see how the animal kingdom on earth developed evolutionarily, in the lower half you can see the development of the plant kingdom. The thicker a grey branch is shown, the greater was the species diversity of the respective class of animals or plants.

Precambrian and Palaeozoic Era

Life probably originated in an environment that prevailed on earth about 3.8 billion years ago. The first simple single-celled organisms from the group of prokaryotes, which are known to us as fossils, date from this time. Later, about 3.5 billion years ago, the first oxygen producers appeared in the form of cyanobacteria. In the following millions of years, the development from single-celled organisms without a nucleus to those with a cell nucleus and finally to multicellular organisms (e.g. eukaryotes) took place very slowly.

After the appearance of the first multicellular organisms towards the end of the Precambrian, the Earth experienced its greatest developmental thrust around 542 million years ago in the course of the "Cambrian Explosion". At that time, the position of the continents was still fundamentally different from today: Apart from Siberia, China and Australia, all large continental masses were located south of the equator, and most of them were united to form one large continent. Under climatically favourable conditions, the basic blueprints of many multicellular animals formed within a few million years in the course of the Cambrian Explosion. The leading fossils of this epoch are the trilobites, which populated the oceans in large numbers and produced the first predatory forms. The evolutionary climax of the Cambrian Explosion was the chordates, the first still very primitive vertebrates.

The beginning of an accelerated evolution among vertebrates was marked by the appearance of the Ostracodermi, the jawless fish. Among the earliest representatives of jawed fish were the armored fish (Placodermi) and spiny sharks (Acanthodii). After countless families and species became extinct at the end of the Ordovician due to a long cold period, an improvement in the climate in the Silurian initiated a turning point in evolutionary history. While in the seas the ammonites, brachiopods, bivalves and fish developed into many forms, the conquest of the mainland announced itself in the extensive shallow water and intertidal zones. The three great continental masses - Siberia and Mongolia, Europe, and North America, and Gondwana, including South America, Africa, Antarctica, Australia and large parts of Asia - moved closer together until they merged completely in the course of the Carboniferous.

Dinosaurs and first mammals

With the beginning of the Mesozoic, climatic conditions changed considerably. The disintegration of Gondwana moved North America and Europe into an arid belt. While the amphibian phylogenetic lineage decreased, reptiles gave rise to many new forms. Some returned to the water, such as the precursors of the earliest crocodiles, turtles, and fish dinosaurs, while pterosaurs conquered the airspace. With the archosaurs, which could reach up to four metres in length, the reign of the dinosaurs began, which produced the largest land creatures of all time and dominated life on earth unchallenged throughout the Mesozoic. An initially inconspicuous line of reptilian evolution led to archaic mammals that lived in the shadow of the giant lizards for millions of years but developed two important evolutionary advantages due to their large number of enemies: keen senses and a large brain.

When the age of the dinosaurs ended around 65 million years ago with a huge extinction event and the Earth's modern era began, the mammals evolved into the most successful class of vertebrates, at times also producing true giants, for example the Asian giant rhinoceros (Inricotherium), up to eight metres long, and the giant sloth (Megatherium), up to six metres long. This large animal fauna, which experienced its peak in the Oligocene and Miocene, died out without leaving any descendants, while the newer forms increasingly prevailed in all vertebrate classes.

With the Neogene, the youngest period in the geological time scale (Miocene, Pliocene, Quaternary) began around 23 million years ago. It extends to the present day and is characterised in terms of the animal world by the further development of birds and the development of mammals. About 7 million years ago, the first representative of hominids appeared in the form of the Central African “Sahelanthropus tchadensisâ€. The first hominids to use self-made tools during the phase of severe climate cooling were probably Homo rudolfensis (2.4 - 1.8 million) and Homo habilis (2.0 - 1.5 million). When Homo sapiens sapiens, the anatomically modern human being, who also came from Africa, reached Europe around 40,000 years ago, he met Neanderthal man here, who disappeared from the Earth 10,000 years later for reasons yet unknown.

Life on land

The pioneers in the colonisation of the mainland were the plants and ferns, slowly followed by the first invertebrate arthropods. The most significant innovation among vertebrates in the Early Devonian was the emergence of the lobe-finned fishes - which still include the coelacanths and lungfishes - some of which evolved the ability to breathe atmospheric air. The first amphibious terrestrial vertebrate is considered to be the ichthyostega, about one metre long, a prehistoric amphibian that colonised shallow water zones towards the end of the Devonian.

After it had taken millions of years for the animal and plant world to conquer the mainland, a tumultuous development began in the lush swamp vegetation of the Carboniferous. A striking feature of plant development was an enormous increase in size. A large number of new forms and phylogenetic lineages were created by the spiders and insects that conquered the airspace during this period. The imposing dragonflies reached wingspans of 75 centimetres. New orders, families and genera were also created by the amphibians. The most important phylogenetic lineage in evolutionary terms led to the reptiles, which differed from their amphibian ancestors in that they laid hard-shelled and nutrient-rich eggs and thus emancipated themselves from the water habitat. The evolutionary advantages of their reproductive strategy became particularly apparent in the following dry periods.